1783, a victory with Hispanic DNA

1783, a victory with Hispanic DNA

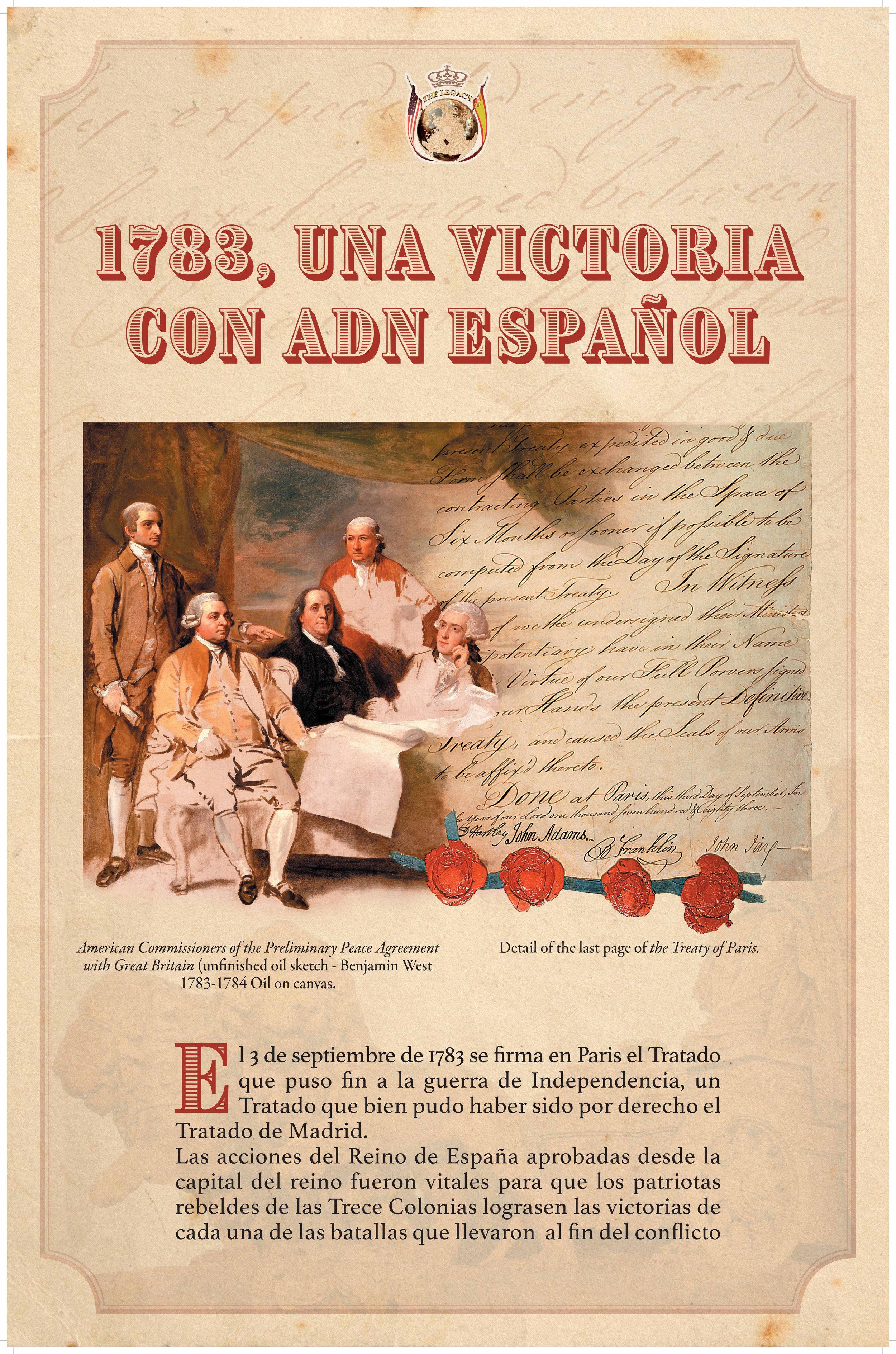

On September 3, 1783, the treaty ending the American Revolutionary War was signed in Paris. The Kingdom of Great Britain was defeated by the Thirteen Colonies, which became the United States of America, occupying the territory from northern Florida to southern Canada. The new nation was formed from the territories located between the Appalachian mountains and the strategic Mississippi River. The rest of the territory remained the Viceroyalty of New Spain covering almost two-thirds of what we know today as the United States. This included the current states of California, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, Oregon, Washington, and Florida. It also partially occupied the states of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana.

On the same day that this treaty was signed, the defeated and humiliated British also signed separate agreements with Spain and France. To each his own, but in typical English style they refused a basic and fair agreement and the Spanish did not manage to recover what was ours by right: Gibraltar, a strategic position without which the British would forever lose control of the Mediterranean. The most notable aspects of the treaty are that we recovered Menorca and western Florida, ceded eastern Florida, and gained the recognition of a debt owed by the victors that was never paid. In a short time, we would go from being essential allies to becoming an obstacle in the expansionist desires of the new nation with a clear strategic objective: control of the Mississippi River.

There is no doubt that the actions of the Kingdom of Spain were vital for the rebel patriots of the Thirteen Colonies to achieve victory. The geostrategic and political landscape of the territory and its inhabitants would have been very different without the military support of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and all the provinces involved. The Spanish contribution included actions that went beyond the wars in the disputed territory. Victories from Lexington to Yorktown required the participation of thousands of Hispanics fighting in other areas of the conflict: the Caribbean, Central America, and the Mediterranean. Spanish soldiers, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Mexicans, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Nicaraguans... fought on sea and land in the service of General Washington's troops.

Since then, and to this day, little or nothing is said about the vital importance of the Spanish armed forces who, on land and sea, were able to blockade the English; nothing is said about the importance of the thousands of Hispanics who supported those military efforts. Nor is enough said about the work of our diplomats and our merchants, nor about the strategic support from our intellectuals and politicians, nor about the fundamental financial support, which was a vital constant in the advance of each of the victories against the English.

The road to victory began on June 21, 1779: King Carlos III declared war on England and sided with the thirteen colonies. The Royal Decree read as follows: "In which, manifesting the just motives of his Royal Resolution of June 21 of this year, authorizes his American vassals, by way of retaliation and redress, to harass by sea and land the subjects of the King of Great Britain."

Spain's support was enormous; the Spanish dominions of America shared a long border in what we know today as the United States of America. The island of Cuba was located just 90 miles from Florida, and its capital, Havana, was a huge base of operations from which to launch major attacks on British territories. It is important to know that Spain had a shipyard there where the ships of the newborn American squadron were being repaired and armed.

The financing of the war was astronomical. The Spanish government made substantial loans to U.S. leaders to defray the cost of the war effort they were deploying against British military forces. The manner of transferring the funds had many variations, most of them carried out discreetly, as it was important to do so without leaving any detectable trace for British agents. It was not an easy task, and in fact it was even done through tax havens. Occasionally, cash deposits were made through bank accounts in neutral countries, usually in the Netherlands, where American agents had money at their disposal. The “peso fuerte” or “real de a ocho”, soon called the Spanish Milled Dollar, became the most popular and commonly used currency among the patriots, since the continental dollar, the currency issued by Congress, suffered continuous devaluations and did not have the strength and backing of Spanish silver. In May 1776, prior to the Declaration of Independence, the Virginia Treasury Department had already approved its issuance.

The Spanish Dollar was of such importance that neither the rebel patriots nor the French soldiers would go out to fight unless their salaries were paid in our currency. Proof of this is that without this economic support, the famous Battle of Yorktown, the last major battle of the conflict, would have been unfeasible.

The Spanish military strategy was overwhelming, and the Spanish provinces had large groups of troops that could and did intervene in the war.

Imagine if Spain had not given its support? Let us suppose Spain had remained neutral and Carlos III had decided not to intervene and had not declared war on Great Britain in 1779.

What would have happened then?

What would have happened without the help provided by the Count of Aranda or without the supplies brought by Diego de Gardoqui?

How would the rebel patriots have fought? What if an uninterrupted stream of weapons, artillery, bayonets, powder, ammunition, tents, uniforms, and medicine through Havana and New Orleans had not nourished and supplied General Washington's volunteers?

What if Spanish King Carlos III had not appointed Juan de Miralles as his delegate, extraordinary diplomatic agent, and plenipotentiary to the Continental Congress? Without that support they would not only have lost one of their main lenders but also the establishment of several trade routes operated by their companies to ship the necessary supplies to the Continental Army,

What would North America be like today... if in the summer of 1780 Admiral Luis de Córdova had not captured the convoy of more than 50 British ships carrying ammunition, supplies, and thousands of British soldiers armed to the teeth to fight against General Washington's troops?

What if the Spanish had not retained thousands of British soldiers in Gibraltar and Central America, who were unable to attack and weaken the rebel troops?

Or if the entire extension of the Spanish Empire in America had not secured the sea and land borders, preventing any maneuver by the British?

Let us imagine that the rebels' rearguard had not been protected by the Gulf Coast to the south and the Mississippi River to the west, which were taken by General Bernardo de Gálvez by his conquest of the English forts and the victories of Mobile and Pensacola?

What would have happened if the Caribbean Sea had been controlled by the British, and the large Spanish islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico had not cooperated?

The answers are rhetorical and do not require a reply: France and Washington's rebel militias could not have won the war. George Washington, his congressmen and his generals, with the support of the French alone, would not have won the final victory and the signing of the Treaty of Paris. If it had taken place, it would have been at a much later date and certainly under different circumstances and consequences.

It took the courage, determination, and resources of the Spaniards; but little or nothing is said about the actions of General Francisco de Saavedra, who promoted solidarity among the merchants of Havana, who in six hours raised more than a million Tours Pounds (Livre tournois) to pay for troops and supplies to win the battle of Yorktown; a sum of money that was enough to sustain an army of 5,000 men for four months.

The list is so exceptional and overwhelming that a large traveling exhibition and a book for the annals of history were essential.

From The Legacy we can say... Mission accomplished!

References:

Dr. Salvador Larrúa-Geudes. Juan de Miralles; Biografía de un padre fundador de los Estados Unidos de América. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; First edición (2016)

Saavedra. Diario de Don Francisco de Saavedra. Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla

United States Congress

(1781 – 1783) The correspondence, journals, committee reports and records of The Continental Congress (1774- 1789)Accounts of the Register office Volume 2

ABC. Digital Lancho J. M. El factor olvidado; la armada española en la independencia de los Estados Unidos. Enero 2015

Armillas J.A. Ayuda secreta y deuda oculta. España y la independencia de los Estados Unidos. Fundación del Cosnejo España Estados Unidos. 2008

Museo Naval. Del Caribe al canal de la Mancha. La Armada Española en la independencia americana. 2022